07 de julho de 2025

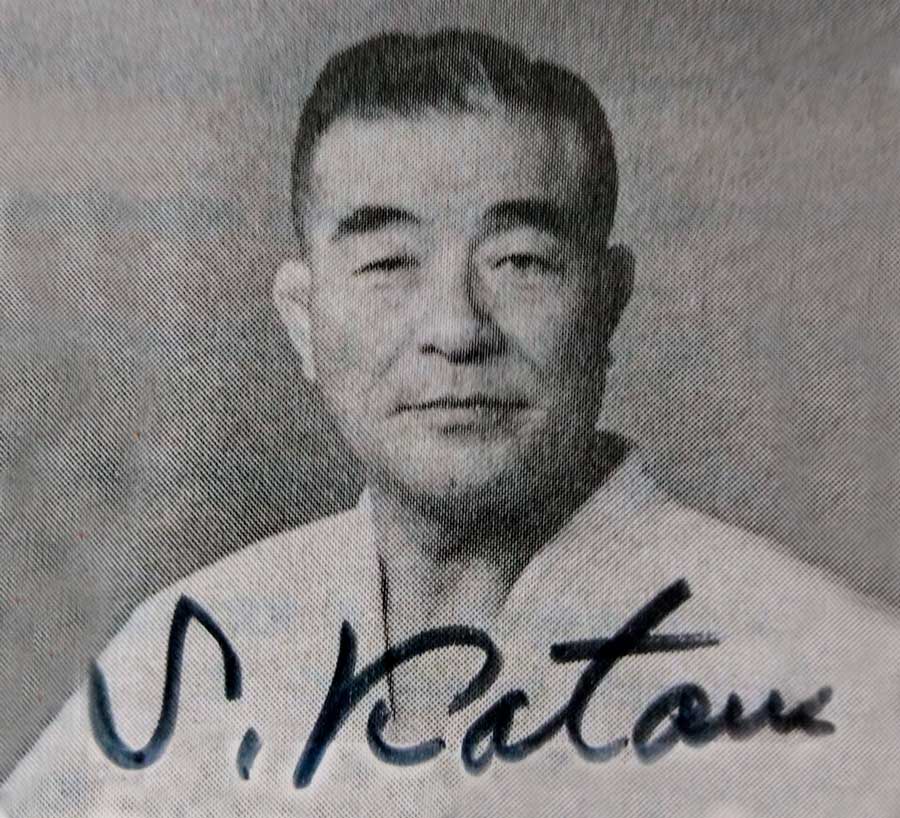

Professor kodansha jū-dan (10th dan) Sumiyuki Kotani

Professor kodansha jū-dan (10th dan) Sumiyuki Kotani

Full mastery of the art of judo is only gained through experience, technical efficiency, time of practice and study, as shown in the scientific literature as proprioceptive information.

Fudo-shim

December 21, 2019

By Prof. Ms. ODAIR BORGES I Photos ARCHIVE

Curitiba – Brazil

I had just arrived in Japan in 1970, annus mirabilis of world judo, and was adapting to Japanese customs, training, and language. I had studied Japanese language in Brazil for a year but living in Japan and speaking Japanese every day resulted to be more difficult than I thought. I was a guest at the Ishii family house in Ashikaga City, Tochigi Prefecture, about 90 kilometers from Tokyo.

Professor Yukiti Ishii and Mrs. Harue Ishii, father and mother of our first Olympic medalist in Brazil, Chiaki Ishii, would be responsible for me in Japan – my parents for a year. After 20 days living in a typical Japanese family house, Yukiti Ishii sensei and I headed to Tokyo for my presentation at Waseda University, where, as a scholarship student, I would do my training. Then we would go to the Kodokan Institute, where I would live and take technical courses.

Born in 1903, the legendary sensei Kotani built one of the most significant trajectories within the Kodokan Institute, dying on October 19, 1991 at the age of 87

At the time, the dream of judokas around the world was to study and practice with great masters Jigoro Kano’s judo at the Kodokan Institute. After all it was a privilege to meet, live, practice and learn from the best in the world, both Japanese and great foreign fighters preparing there for the 1971 World Judo Championships and the official premiere of Judo at the 1972 Munich Olympic Games. At the age of 22, I was san-dan (Kodokan), three-time champion of São Paulo state tournament, Brazilian vice-champion and member of the Brazilian judo team.

At Waseda University we were welcomed by the sensei Yoshimi Ozawa, today jū-dan (10th dan), and the students of the judo club, whose captain was Toyoji Matsumoto, who I’m still in touch with up to today. Chiaki Ishii and his brother Isamu Ishii also graduated from Waseda.

At Kodokan, Ishii Yukiti sensei and I, were greeted by the foreign department director, the sensei Sumiyuki Kotani, a red belt, who was still kyū-dan (9th dan) at the time. My first impression was that he was around 60 years old, but he was actually 66 years old. After the usual formalities, he informed me of the nage-no-kata, katame-no-kata and nage-waza compulsory classes and courses, respectively, with the teachers. Kotani, Toshiro Daigo, Yoshimi Ozawa and Ichiro Abe, with whom I had the honor to live and learn.

There would be classes and training every day from Monday to Saturday. In addition, we followed the calendar of the monthly tsukinami-shiai and kohaku-shiai competitions and the summer and winter courses.

Once the schedule was defined, ending the conversation, Kotani sensei told me: “Many foreigners come to Japan to train and learn judo, but they will not succeed if they do not understand the way of Japanese judo is practiced.” This was the first lesson.

Alone in Tokyo and already settled in my Kodokan apartment the next day after my first university training with two hours of randori, I returned to Kodokan for the first nage-no-kata class with Daigo sensei. After class I went to the main dojo, made up of 500 tatami – now known to many Brazilians. By the way, I was the first Brazilian to go through the training internship at a Japanese university, living and studying at the Kodokan Institute for a year.

At the dojo, I found Kotani sensei, now wearing judogi. I had never seen a red belt before and much less in randori. In Brazil, I rarely saw a red and white belt, the kodansha teacher (kohaku obi sensei). For these things that sometime happen by chance and we cannot explain, he came, walking slowly, looking in my direction, a trace of a smile on his lips and called me: “Odairu!” I answered quickly: “Hai,” as I had already been oriented.

Then praised my ukemi and in the silence of his presence I only heard him say, “Sukoshi yateru ka?” (Let’s practice a little). He showed me how to do the greeting in that dojo, assuming a characteristic gesture, and I anticipated that I would be my partner of randori at that moment. I was taken aback and needed a few seconds to reach full understanding of this moment, and at the same time, of this privilege.

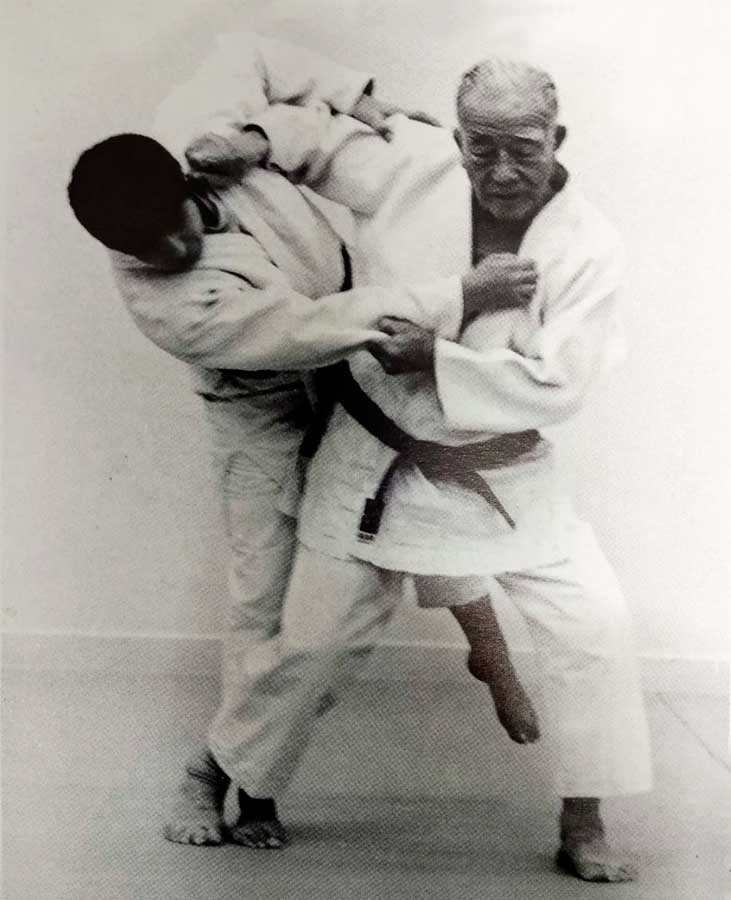

With one firm hand he grasped my left judogi collar and with the other hand with the same energy he pinned my sleeve. I did the same and heard, “Let’s just walk the tatami, and you give the directions.” We walked for about three minutes, moving forward, backward, and sideways; every so often he would stop, shift his grip to the left, change the position of his legs, and restart.

I just asked myself: “What is his intention?” and “what kind of practice in this that I never have seen before?” We stopped, and he said: “Odairu, your favorite technique is uchi-mata and also intends to apply o-uchi-gari.” That scared me! After all, he had never seen me fight and didn’t even know me. But he was right!

“Use only the necessary force. It is as if you are holding a live fish: if you squeeze it too much, it dies; If you don’t hold it properly, it runs away. Feel your opponent in the hands. Understand judo, dedicate yourself and strive to exhaustion.”

Then he said to me, “Take me down with your tokui-waza (favorite technique).” Not knowing what to do, with the caution that common sense recommends and respecting the limits that this man’s age imposed, I applied a low-intensity uchi-mata. He shook my judogi by the collar and sleeve and in a louder tone asked, “Odairu! What is this? Apply your technique! Do it!”

Frightened, I didn’t even think and grabbed his judogi really hard. I also heard: “Your grab is very strong; in judo there is no need for that; and judo is not meant to strengthen muscles”. I applied my uchi-mata as I was technically guided by Ishii sensei here in Brazil, with speed and strength to knock him on the tatami. Continuously, his gesture was instinctive, automatic, reflexive, and the retaliation came in uchi-mata-sukashi.

To this day I have not assimilated, nor did I understand where so much skill, softness and harmony came from that counterattack that simply plunged me on the tatami. When I got up, he said to me: “Use only the necessary force. It is as if you are holding a live fish: if you squeeze it too much, it dies; If you don’t hold it properly, it runs away. Feel your opponent in the hands. Understand judo, dedicate yourself and strive to exhaustion. ”

I was amazed and impressed by the sensitivity with which Kotani sensei sensed, analyzed and diagnosed my favorite techniques by just walking and doing kumi-kata.

After a brief reflection, I concluded: this is the full mastery of the art of judo, acquired by experience, technical efficiency, time of practice and study, as also shown in the scientific literature as proprioceptive information.

This ended our first randori session. After the greeting, he left as he arrived, slowly. The next day I found out about an information that motivated me a lot: Kotani sensei was the last remaining living disciple of Master Jigoro Kano.

In my heart I am proudly preserving this honor and privilege. Opportunity of the few and my greatest trophy.

“A tale must always be a story that lingers in our minds without spoiling over time, easy to remember and passed on.”

Mário Palmério

07 de julho de 2025

05 de julho de 2025

02 de julho de 2025